History of Finland

|

|---|

| This article is part of the Scandinavia series |

| Geography |

|

| Viking Age |

|

| Political entities |

|

| History of Scandinavia |

| Other |

|

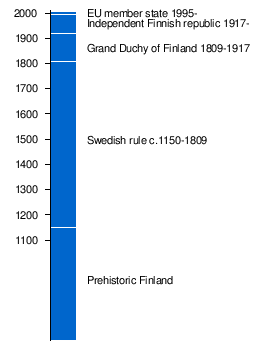

The land area that now makes up Finland was settled immediately after the Ice Age, beginning from around 8500 BCE. Most of the region was part of the Kingdom of Sweden from the 13th century to 1809, when it was ceded to the Russian Empire, becoming the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland. The catastrophic Finnish famine of 1866–1868 was followed by eased economic regulation and political development.

In 1917, Finland declared independence. A civil war between the Finnish Red Guards and the White Guard ensued a few months later with the "Whites" gaining the upper hand. After the internal affairs stabilized, the still mainly agrarian economy grew relatively fast. Relations with the West, especially Sweden and the United Kingdom, were strong but the pre-World War II relations with the socialist Soviet Union remained weaker. During the Second World War, Finland fought twice against the Soviet Union, and had to cede most of Karelia to the USSR, but remained an independent democracy. During the Cold War an Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance existed between the Soviet Union and Finland and such phenomena as finlandization and radical socialism such as "taistolaisuus" were part of internal affairs. President Urho Kekkonen's tenure lasted 25 years, from 1956 until 1981.

Throughout its independent history, Finland has maintained a capitalist economy. Its GDP per capita has been among the world's highest since the 1970s. Between 1970 and 1990, the number of public sector employees and the tax burden increased more than nearly any other Western country. In 1992 Finland simultaneously faced economic overheating and depressed Western, Soviet and local markets. The country joined the European Union in 1995. According to a 2005 poll, most Finns are reluctant to join NATO.[1]

Prehistory

Paleolithic

If confirmed, the oldest archeological site in Finland would be the Wolf Cave in Kristinestad, Ostrobothnia. Excavations are underway and if the so far presented estimates hold true, it would be the only pre-glacial (Neanderthal) site so far found in the Nordic countries and some 130 000 years old [3].

Mesolithic

The earliest traces of modern humans are known from ca. 8500 BCE and are post-glacial. The people were first probably seasonal hunter-gatherers. Their items are known as the Suomusjärvi culture and the Kunda culture. Among the finds is the net of Antrea, one of the oldest fishing nets ever excavated (calibrated carbon dating: ca. 8300 BCE).

Neolithic

Around 5300 BCE pottery appeared in Finland. The earliest representatives belong to the Comb Ceramic Cultures, known for their distinctive decorating patterns. This marks the beginning of the neolithic for Finland, although the subsistence was still based on hunting and fishing. Extensive networks of exchange existed across Finland and Northeastern Europe during 5th millennium BCE. For example flint from Scandinavia and Valdai Hills, amber from Scandinavia and the Baltic region, and slate from Scandinavia and Lake Onega found their way into Finnish archeological sites and asbestos and soap stone from e.g. Saimaa spread outside of Finland. Rock paintings, apparently related to shamanistic and totemistic belief systems, have been found especially in Eastern Finland, e.g. Astuvansalmi.

From 3200 BCE onwards either immigrants or a strong cultural influence from south of the Gulf of Finland settled in southwestern Finland. This culture was a part of the European Battle Axe cultures, which have often been associated with the movement of Indo-European speakers. The Battle-Axe or Cord Ceramic culture seems to have practiced agriculture and animal husbandry outside of Finland but the earliest confirmed traces of agriculture in Finland date later, approximately to the 2nd millennium BCE. Further inland the societies retained their hunting-gathering lifestyles.

The Battle axe and the Comb Ceramic cultures merged giving rise to the Kiukainen culture which existed between 2300 BCE and 1500 BCE featuring fundamentally a comb ceramic tradition with cord ceramic characteristics.

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age began some time after 1500 BCE. The coastal regions of Finland were a part of the Nordic Bronze Culture, whereas in the inland regions the influences came from the bronze-using cultures of Northern and Eastern Russia.

Chronology of the Finno-Ugric, Finnic, Indo-European and Germanic languages in Finland

The question of the time lines for the evolution and spread of the contemporary languages is controversial and new theories challenging older postulations have been introduced continuously.

According to the currently most widespread presumption,[2][3][4] Finno-Ugric (or Uralic) languages were first spoken in Finland and the adjacent areas during the (typical) Comb Ceramic period, around 4000 BCE at the latest. During the 2nd millennium BCE these evolved – possibly under an Indo-European (most likely Baltic) influence – into proto-Sami (inland) and proto(-Baltic)-Finnic (coast). However, recently this theory has been increasingly contested among comparative linguists.[5] It has been suggested that the Finno-Ugrian languages arrived in Finland later, perhaps during the Bronze Age.[6] The Finnish language is thought to have started to differentiate during the Iron Age starting from the first centuries AD onwards.

Cultural influences from all points of the compass are visible in Finnish archeological finds from the very first settlements onwards. E.g. archaeological finds from Finnish Lapland suggest the presence of the Komsa culture. The Sujala finds equal in age with the earliest Komsa-artefacts from Norway but may suggest also a connection to the Swiderian culture.[7] South-Western Finland belonged to the Nordic Bronze Age, which may be associated with Indo-European languages and according to Finnish Germanist Jorma Koivulehto speakers of Proto-Germanic language in particular. Artefacts found in Kalanti and the province of Satakunta, for long monolingually Finnish, and their place-names have made several scholars argue for an existence of a proto-Germanic speaking population component a little later, during the Early and Middle Iron Age.[8][9] Some claim a Norse-speaking population settled parts of Finland's coastal areas in the 12th to 13th centuries.[10] Swedish language differentiated from the eastern Norse dialects by the 13th century. During the subsequent Swedish reign over Finland particularly the coastal areas witnessed waves of settlement from Sweden.

Iron Age

The Iron Age in Finland is considered to last from c.500 BCE until c.1150 AD when the Swedish Conquest of Finland was complete and written history in Finland (the Middle Ages) begins. There is no evidence of any form of writing in Finland, runes or otherwise, prior to the Swedish Conquest and all evidence regarding Finnish history prior to Swedish involvement is based on archaeological findings and the scant records of contemporaneous third parties.

The three main dialectal groups of Finnish-speakers, (proper-)Finns, Tavastians and Karelians probably emerged during the Iron Age. The archaeological culture of the Åland Islands had a more prominent Swedish character than the rest of the country, possibly suggesting Scandinavian settlement.

The earliest findings of imported iron blades and local iron working appear in 500 BCE. From about 50 AD, there are indications of a more intense long-distance exchange of goods in coastal Finland. Inhabitants traded their products, presumably, mostly furs, for weapons and ornaments with the Balts and the Scandinavians as well as with the peoples along the traditional eastern trade routes. The existence of richly furnished burials, usually with weapons, suggests that there was a chiefly elite in some parts of the country. Hillforts spread over most of southern Finland at the end of the Iron and early Medieval Age. There is no evidence of state formation although there are a few referrals to kings ruling in Finland in Norse sagas.

In the early Iron Age a word similar to Finns appeared for the first time in a written document when Tacitus mentions Fenni in his Germania. However, it is unclear if these have anything to do with the present Finnish people. The first Scandinavian documents mentioning a "land of the Finns" are two runestones: (Söderby, Sweden, with the inscription finlont (U 582 †), Gotland with the inscription finlandi (G 319 M) dating from the eleventh century.[11]

The Middle Ages

Contact between Sweden and what is now Finland was considerable even during pre-Christian times – the Vikings were known to Finns both due to their participation in commerce and plundering. There is no commonly accepted evidence of Viking settlement in the Finnish mainland, although some finds in Southern Ostrobothnia have caused controversy.[12] The Åland Islands probably had Swedish settlement during the Viking Period. However, some scholars claim that the archipelago was deserted during the 11th century. Åland was then re-settled by Swedes during the 12th century.

According to the archaeological finds, Christianity gained a foothold in Finland during the 11th century. According to the very few written documents that have survived, the church in Finland was still in its early development in the 12th century. Later medieval legends describe Swedish attempts to conquer and Christianize Finland sometime in the mid-1150s. In the early 13th century, Bishop Thomas became the first bishop of Finland. There were several secular powers who aimed to bring the Finns under their rule. These were Sweden, Denmark, the Republic of Novgorod in Northwestern Russia and probably the German crusading orders as well. Finns had their own chiefs, but most probably no central authority. Russian chronicles indicate there were conflict between Novgorod and the Finnic tribes from the 11th or 12th century to the early 13th century.

The name "Finland" originally signified only the southwestern province that has been known as "Finland Proper" since the 18th century. Österland (lit. Eastern Land) was the original name for the Swedish realm's eastern part, but already in the 15th century Finland began to be used synonymously with Österland. The concept of a Finnish "country" in the modern sense developed only slowly during the period of the 15th–18th centuries.

It was the Swedish regent, Birger Jarl, who established Swedish rule in Finland through the Second Swedish Crusade, most often dated to 1249, which was aimed at Tavastians who had stopped being Christian again. Novgorod gained control in Karelia, the region inhabited by speakers of Eastern Finnish dialects. Sweden however gained the control of Western Karelia with the Third Finnish Crusade in 1293. Western Karelians were from then on viewed as part of the western cultural sphere, while eastern Karelians turned culturally to Russia and Orthodoxy. While eastern Karelians remain linguistically and ethnically closely related to the Finns, they are considered a people of their own by most. Thus, the northern border between Catholic and Orthodox Christendom came to lie at the eastern border of what would become Finland with the Treaty of Nöteborg in 1323.

During the 13th century, Finland was integrated into medieval European civilization. The Dominican order arrived in Finland around 1249 and came to exercise huge influence there. In the early 14th century, the first documents of Finnish students at Sorbonne appear. In the south-western part of the country, an urban settlement evolved in Turku. Turku was one of the biggest towns in the Kingdom of Sweden, and its population included German merchants and craftsmen. Otherwise the degree of urbanization was very low in medieval Finland. Southern Finland and the long coastal zone of the Bothnian Gulf had a sparse farming settlement, organized as parishes and castellanies. In the other parts of the country a small population of Sami hunters, fishermen and small-scale farmers lived. These were exploited by the Finnish and Karelian tax collectors. During the 12th and 13th centuries, great numbers of Swedish settlers moved to the southern and north-western coasts of Finland, to the Åland Islands and to the archipelago between Turku and the Åland Islands: in these regions, the Swedish language is widely spoken even today. Swedish came to be the language of the high-status people in many other parts of Finland as well.

During the 13th century, the bishopric of Turku was established. The cathedral of Turku was the center of the cult of Saint Henry, and naturally the cultural center of the bishopric. The bishop had the ecclesiastical authority over much of today's Finland and was usually the most powerful man there. Bishops were often Finns, whereas the commanders in the castles were more often Scandinavian or German noblemen. In 1362, representatives from Finland were called to participate in the elections for king of Sweden. That year is often held to signify the incorporation of Finland into the kingdom of Sweden. As in the Scandinavian part of the kingdom, a gentry or (lower) nobility consisted of magnates and yeomen who could afford armament for a man and a horse. These were concentrated in the southern part of Finland.

The strong fortress of Vyborg (Finnish: Viipuri, Swedish: Viborg) guarded the eastern border of Finland. Sweden and Novgorod signed the Treaty of Nöteborg (Pähkinäsaari in Finnish) in 1323, but that would not last long. For example, in 1348 the Swedish king Magnus Eriksson staged a failed crusade against the Orthodox "heretics", managing only to alienate his supporters and finally losing his crown. The bones of contention between Sweden and Novgorod were the northern coast-line of the Bothnian Gulf and the wilderness regions of Savo in Eastern Finland. Novgorod considered these as hunting and fishing grounds of its Karelian subjects, protesting against the slow infiltration of Catholic settlers from the West. Occasional raids and clashes between Swedes and Novgorodians occurred during the late 14th and 15th centuries, but for most of the time an uneasy peace prevailed. There existed internal tensions as well. During the 1380s a civil war in the Scandinavian part of Sweden brought unrest to Finland, too. The victor of this struggle was Queen Margaret I of Denmark, who brought the three Scandinavian kingdoms of Sweden, Denmark and Norway under her rule (the "Kalmar Union") in 1389. The next 130 years or so were characterized by attempts of different Swedish factions to break out of the Union. Finland was sometimes involved in these struggles, but in general the 15th century seems to have been a relatively prosperous time, characterized by population growth and economic development. Towards the end of the century, however, the situation on the eastern border was becoming more tense. The Principality of Moscow conquered Novgorod, preparing the way for a unified Russia, and soon tensions arose with Sweden. In 1495–1497, a war between Sweden and Russia was fought. The fortress-town of Vyborg stood against a Russian siege: according to a contemporary legend, it was saved by a miracle.

The 16th century

In 1521 the Kalmar Union collapsed and Gustav Vasa became the King of Sweden. During his rule, the Swedish church was reformed (1527). The state administration underwent extensive reforms and development too, giving it a much stronger grip on the life of local communities – and ability to collect higher taxes. Following the policies of the Reformation, in 1551 Mikael Agricola, bishop of Turku, published his translation of the New Testament into the Finnish language.

In 1550 Helsinki was founded by Gustav Vasa under the name of Helsingfors, but remained little more than a fishing village for more than two centuries.

King Gustav Vasa died in 1560 and his crown was passed to his three sons in separate turns. King Erik XIV started an era of expansion when the Swedish crown took the city of Tallinn in Estonia under its protection in 1561. The Livonian War was the beginning of a warlike era which lasted for 160 years. In the first phase, Sweden fought for the lordship of Estonia and Latvia against Denmark, Poland and Russia. The common people of Finland suffered because of drafts, high taxes, and abuse by military personnel. This resulted in the Cudgel War of 1596–97, a desperate peasant rebellion, which was suppressed brutally and bloodily. A peace treaty (the Treaty of Teusina) with Russia in 1595 moved the border of Finland further to the east and north, very roughly where the modern border lies.

An important part of the 16th century history of Finland was growth of the area settled by the farming population. The crown encouraged farmers from the province of Savonia to settle the vast wilderness regions in Middle Finland. This was done, and the original Sami population often had to leave. Some of the wilderness settled was traditional hunting and fishing territory of Karelian hunters. During the 1580s, this resulted in a bloody guerrilla warfare between the Finnish settlers and Karelians in some regions, especially in Ostrobothnia.

The 17th century – the Swedish Empire

In 1611-1632 Sweden was ruled by King Gustavus Adolphus, whose military reforms transformed the Swedish army from a peasant militia into an efficient fighting machine, possibly the best in Europe. The conquest of Livonia was now completed, and some territories were taken from internally divided Russia in the Treaty of Stolbova. In 1630, the Swedish (and Finnish) armies marched into Central Europe, as Sweden had decided to take part in the great struggle between Protestant and Catholic forces in Germany, known as the Thirty Years' War. The Finnish light cavalry was known as the Hakkapeliitat.

After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the Swedish Empire was one of the most powerful countries in Europe. During the war, several important reforms had been made in Finland:

- 1637–1640 and 1648–1654 Count Per Brahe functioned as general governor of Finland. Many important reforms were made and many towns were founded. His period of administration is generally considered very beneficial to the development of Finland.

- 1640 Finland's first university, the Academy of Åbo, was founded in Turku at the proposal of Count Per Brahe by Queen Christina of Sweden.

- 1642 The whole Bible was published in Finnish.

However, the high taxation, continuing wars and the cold climate (the Little Ice Age) made the Imperial era of Sweden rather gloomy times for Finnish peasants. In 1655–1660, the Northern Wars were fought, taking Finnish soldiers to the battle-fields of Livonia, Poland and Denmark. In 1676, the political system of Sweden was transformed into an absolute monarchy.

In Middle and Eastern Finland, great amounts of tar were produced for export. European nations needed this material for the maintenance of their fleets. According to some theories, the spirit of early capitalism in the tar-producing province of Ostrobothnia may have been the reason for the witch-hunt wave that happened in this region during the late 17th century. The people were developing more expectations and plans for the future, and when these were not realized, they were quick to blame witches – according to a belief system the Lutheran church had imported from Germany.

The Empire had a colony in the New World in the modern-day Delaware-Pennsylvania area between 1638–1655. At least half of the immigrants were of Finnish origin.

The 17th century was an era of very strict Lutheran orthodoxy. In 1608, the law of Moses was declared the law of the land, in addition to secular legislation. Every subject of the realm was required to confess the Lutheran faith and church attendance was mandatory. Ecclesiastical penalties were widely used.[13] The rigorous requirements of orthodoxy were revealed in the dismissal of the Bishop of Turku, Johan Terserus, who wrote a catechism which was decreed heretical in 1664 by the theologians of the Academy of Åbo.[14] On the other hand, the Lutheran requirement of the individual study of Bible prompted the first attempts at wide-scale education. The church required from each person a degree of literacy sufficient to read the basic texts of the Lutheran faith. Although the requirements could be fulfilled by learning the texts by heart, also the skill of reading became known among the population.[15]

In 1697–99, a famine caused by climate killed approximately 30% of the Finnish population. Soon afterwards, another war determining Finland's fate began (the Great Northern War of 1700–21).

The 18th century – the Age of Enlightenment

During the Great Northern War (1700–1721), Finland was occupied by the Russians and the south-eastern part, including the town of Vyborg, was annexed by Russia after the Treaty of Nystad. The border with Russia came to lie roughly where it returned to after World War II. Sweden's status as a European great power was lost, and Russia was now the leading power in the North. The absolute monarchy was ended in Sweden. During this Age of Liberty, the Parliament ruled the country, and the two parties of the Hats and Caps struggled for control leaving the lesser Court party, i.e. parliamentarians with close connections to the royal court, with little to no influence. The Caps wanted to have a peaceful relationship with Russia and were supported by many Finns, while other Finns longed for revenge and supported the Hats.

Finland by this time was not a populous land. By the mid-18th century, the population was less than 470 000 according to official statistics (based on (Lutheran) church records, so a few Orthodox Christian parishes in Northern Karelia are not included). However the population grew rapidly, and doubled before the turn of the century. 90% of the population were typically classified as "peasants", most being free taxed yeomen. Society was divided into four Estates: peasants (free taxed yeomen), the clergy, nobility and burghers. A minority, mostly cottagers, were estateless, and had no political representation. Forty-five percent of the male population were enfranchised with full political representation in the legislature – although clerics, nobles and townsfolk had their own chambers in the parliament, boosting their political influence and excluding the peasantry on matters of foreign policy.

The mid-18th century was a relatively good time, partly because life was now more peaceful. However, during the Lesser Wrath (1741–1742), Finland was again occupied by the Russians after the government, during a period of Hat party dominance, had made a botched attempt to reconquer the lost provinces. Instead the result of the Treaty of Åbo was that the Russian border was moved further to the west. During this time, Russian propaganda hinted at the possibility of creating a separate Finnish kingdom.

Both the ascending Russian Empire and pre-revolutionary France aspired to have Sweden as a client state. Parliamentarians and others with influence were susceptible to taking bribes which they did their best to increase. The integrity and the credibility of the political system waned, and in 1771 the young and charismatic king Gustav III staged a coup d'état, abolished parliamentarism and reinstated royal power in Sweden – more or less with the support of the parliament. In 1788, he started a new war against Russia. Despite a couple of victorious battles, the war was fruitless, managing only to bring disturbance to the economic life of Finland. The popularity of King Gustav III waned considerably. During the war, a group of officers made the famous Anjala declaration demanding peace negotiations and calling of Riksdag (Parliament). An interesting sideline to this process was the conspiracy of some Finnish officers, who attempted to create an independent Finnish state with Russian support. After an initial shock, Gustav III crushed this opposition. In 1789, the new constitution of Sweden strengthened the royal power further, as well as improving the status of the peasantry. However, the continuing war had to be finished without conquests – and many Swedes now considered the king as a tyrant.

With the interruption of the war (1788–1790), the last decades of the 18th century had been an era of development in Finland. New things were changing even everyday life, such as starting of potato farming after the 1750s. New scientific and technical inventions were seen. The first hot air balloon in Finland (and in the whole Swedish kingdom) was made in Oulu (Uleåborg) in 1784, only a year after it was invented in France. Trade increased and the peasantry was growing more affluent and self-conscious. The Age of Enlightenment's climate of broadened debate in the society on issues of politics, religion and morals would in due time highlight the problem that the overwhelming majority of Finns spoke only Finnish, but the cascade of newspapers, belles-lettres and political leaflets was almost exclusively in Swedish – when not in French.

The two Russian occupations had been harsh and were not easily forgotten. These occupations were a seed of a feeling of separateness and otherness, that in a narrow circle of scholars and intellectuals at the university in Turku was forming a sense of a separate Finnish identity representing the eastern part of the realm. The shining influence of the Russian imperial capital Saint Petersburg was also much stronger in southern Finland than in other parts of Sweden, and contacts across the new border dispersed the worst fears for the fate of the educated and trading classes under a Russian régime. At the turn of the century, the Swedish-speaking educated classes of officers, clerics and civil servants were mentally well prepared for a shift of allegiance to the strong Russian Empire.

King Gustav III was assassinated in 1792, and his son Gustav IV Adolf assumed the crown after a period of regency. The new king was not a particularly talented ruler; at least not talented enough to steer his kingdom through the dangerous era of the French Revolution and Napoleonic wars.

Meanwhile, the Finnish areas belonging to Russia after the peace treaties in 1721 and 1743 (not including Ingria), called "Old Finland" were initially governed with the old Swedish laws (a not uncommon practice in the expanding Russian Empire in the 18th century). However, gradually the rulers of Russia granted large estates of land to their non-Finnish favorites, ignoring the traditional landownership and peasant freedom laws of Old Finland. There were even cases where the noblemen punished peasants corporally, for example by flogging. The overall situation caused decline in the economy and morale in Old Finland, worsened since 1797 when the area was forced to send men to the Imperial Army. The construction of military installations in the area brought thousands of non-Finnish people to the region. In 1812, after the Russian conquest of Finland, "Old Finland" was rejoined to the rest of the country but the landownership question remained a serious problem until the 1870s.

Russian Grand Duchy

During the Finnish War between Sweden and Russia, Finland was again conquered by the armies of Tsar Alexander I. The four Estates of occupied Finland were assembled at the Diet of Porvoo on March 29, 1809 to pledge allegiance to Alexander I of Russia. Following the Swedish defeat in the war and the signing of the Treaty of Fredrikshamn on September 17, 1809, Finland remained an autonomous Grand Duchy in the Russian Empire until the end of 1917, with Karelia ( "Old Finland") handed back to Finland in 1812. During the years of Russian rule the degree of autonomy varied. Periods of censorship and political prosecution occurred, particularly in the two last decades of Russian control, but the Finnish peasantry remained free (unlike their Russian counterparts) as the old Swedish law remained effective (including the relevant parts from Gustav III's Constitution of 1772). The old four-chamber Diet was re-activated in the 1860s agreeing to supplementary new legislation concerning internal affairs. Industrialisation begun during the 19th century from forestry to industry, mining and machinery and laid the foundation of Finland's current day prosperity, even though agriculture employed a relatively large part of the population until the post-World War II era.

Nationalism

Particularly following Finland's incorporation into the Swedish central administration during the 16th and 17th centuries, Swedish had been the dominant language in administration and education. Before that, German, Latin and Swedish were important languages beside native-spoken Finnish. Finnish recovered its predominance after a 19th-century resurgence of Finnish Nationalism, and Russian controllers working to separate Finns from Sweden and to ensure the Finns' loyalty.

The publication in 1835 of the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, a collection of traditional myths and legends which is the folklore of the Karelian people (the Finnic Russian Orthodox people who inhabit the Lake Ladoga-region of eastern Finland and present-day NW Russia), stirred the nationalism that later led to Finland's independence from Russia. The Finnish national awakening in the mid-19th century was the result of members of the Swedish-speaking upper classes deliberately choosing to promote Finnish culture and language as a means of nation building, i.e. to establish a feeling of unity between all people in Finland including (and not of least importance) between the ruling elite and the ruled peasantry.

In 1863, the Finnish language gained a position in administration, and 1892 Finnish finally became an equal official language and gained a status comparable to that of Swedish. Within a generation Finnish clearly dominated in government and society.

Russification

Democratic change

In 1906, as a result of the Russian Revolution of 1905 and the associated Finnish general strike of 1905, the old four-chamber Diet was replaced by a unicameral Parliament of Finland (the "Eduskunta"). For the first time in the world, universal suffrage (right to vote) and eligibility was implemented to include women: Finnish women were the first in the world to gain full eligibility to vote; and have membership in an estate; land ownership or inherited titles were no longer required. However, on the local level things were different, as in the municipal elections the number of votes was tied to amount of tax paid. Thus, rich people could cast a number of votes, while the poor perhaps none at all. The municipal voting system was changed to universal suffrage in 1917 when a left-wing majority was elected to Parliament.

Independence and Civil War

In the aftermath of the February Revolution in Russia, Finland received a new Senate, a coalition-Cabinet with the same power structure as the Finnish Parliament. Based on the general election in 1916, the Social Democrats had a small majority, and the Social Democrat Oskari Tokoi became Prime Minister. The new Senate was willing to cooperate with the provisional government of Russia, but no agreement was reached. Finland considered the personal union with Russia to be over after the dethroning of the Tsar – although the Finns had de facto recognized the provisional government as the Tsar's successor by accepting its authority to appoint a new Governor General and Senate. They expected the Tsar's authority to be transferred to Finland's Parliament, which the provisional government of Russia refused, suggesting instead that the question should be settled by the Russian Constituent Assembly. For the Finnish Social Democrats it seemed as though the Russian bourgeoisie was an obstacle on Finland's road to independence as well as on the proletariat's road to justice. The non-Socialists in Tokoi's Senate were, however, more confident. They and most of the non-Socialists in the Parliament, rejected the Social Democrats' proposal on parliamentarism (the so-called "Power Act") as being too far-reaching and provocative. The act restricted Russia's influence on domestic Finnish matters, but didn't touch the Russian government's power on matters of defence and foreign affairs. For the Russian Provisional government this was, however, far too radical. As the Parliament had exceeded its authority, it was dissolved.

The minority of the Parliament, and of the Senate, were content. New elections promised a chance to gain majority, which they were convinced would improve the chances to reach an understanding with Russia. The non-Socialists were also inclined to cooperate with the Russian Provisional government because they feared the Socialists' power would grow, resulting in radical reforms, such as equal suffrage in municipal elections, or a land reform. The majority had the completely opposite opinion. They didn't accept the Provisional government's right to dissolve the Parliament.

The Social Democrats held on to the Power Act and opposed the promulgation of the decree of dissolution of the Parliament, whereas the non-Socialists voted for promulgating it. The disagreement over the Power Act led to the Social Democrats leaving the Senate. When the Parliament met again after the summer recess in August 1917, only the groups supporting the Power Act were present. Russian troops took possession of the chamber, the Parliament was dissolved, and new elections were carried out. The result was a (small) non-Socialist majority and a purely non-Socialist Senate. The suppression of the Power Act, and the cooperation between Finnish non-Socialist forces and oppressive Russia provoked great bitterness among the Socialists, and had resulted in dozens of politically motivated terror assaults, including murders.

Independence

The October Revolution turned Finnish politics upside down. Now, the new non-Socialist majority of the Parliament desired total independence, and the Socialists came gradually to view Soviet Russia as an example to follow. On November 15, 1917, the Bolsheviks declared a general right of self-determination, including the right of complete secession, "for the Peoples of Russia". On the same day the Finnish Parliament issued a declaration by which it assumed, pro tempore, all powers of the Sovereign in Finland.

Worried by the development in Russia, and Finland, the non-Socialist Senate proposed that Parliament declare Finland's independence, which was agreed on in the Parliament on December 6, 1917. On December 18 (December 31 N. S.) the Soviet government issued a Decree, recognizing Finland's independence, and on December 22 (January 4, 1918 N. S.) it was approved by the highest Soviet executive body – VTsIK. Germany and the Scandinavian countries followed without delay.

From January to May 1918, Finland experienced the brief but bitter Finnish Civil War that colored domestic politics and the foreign relations of Finland for many years to come. On one side there were the "white" civil guards, who fought for the anti-Socialists. On the other side were the Red Guards, which consisted of workers and tenant farmers. The latter proclaimed a Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic. The defeat of the Red Guards was achieved with support from Imperial Germany. Neighboring Sweden was in the midst of her own process of democratization, with socialists in government for the first time. For many decades, Finns on both sides remained bitter over Sweden's reluctance to become involved in the Civil War.

During the Civil War, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed between the Central Powers and Bolshevist Russia, stating the following regarding Finland:

- Finland and the Åland Islands will immediately be cleared of Russian troops and the Russian Red Guard, and the Finnish ports of the Russian fleet and of the Russian naval forces. So long as the ice prevents the transfer of warships into Russian ports, only limited forces will remain on board the warships. Russia is to put an end to all agitation or propaganda against the Government or the public institutions of Finland.

- The fortresses built on the Åland Islands are to be removed as soon as possible. As regards the permanent non-fortification of these islands as well as their further treatment in respect to military technical navigation matters, a special agreement is to be concluded between Germany, Finland, Russia, and Sweden; there exists an understanding to the effect that, upon Germany's desire, still other countries bordering upon the Baltic Sea would be consulted in this matter.

Finland in the inter-war era

Despite the Declaration of Independence calling Finland a Republic, after the civil war the parliament, cleared of its Social Democrat members, and with a narrow majority voted to establish the Kingdom of Finland. Frederick Charles of Hesse, a German prince, was elected King, putatively with the name Väinö I of Finland, with Pehr Evind Svinhufvud and General Mannerheim serving as Regents. However, Germany's defeat in World War I meant that the idea was abandoned. Finland instead became a republic, with Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg elected as its first President in 1919.

The new republic faced a dispute over the Åland Islands, which were overwhelmingly Swedish-speaking and sought retrocession to Sweden. However, as Finland was not willing to cede the islands, they were offered an autonomous status. Nevertheless, the residents did not approve the offer, and the dispute over the islands was submitted to the League of Nations. The League decided that Finland should retain sovereignty over the Åland Islands, but they should be made an autonomous province. Thus Finland was under an obligation to ensure the residents of the Åland Islands a right to maintain the Swedish language, as well as their own culture and local traditions. At the same time, an international treaty was concluded on the neutral status of Åland, under which it was prohibited to place military headquarters or forces on the islands.

Directly after the Civil War there were many incidents along the border between Finland and Soviet Russia, such as the Aunus expedition and the Pork mutiny. Relations with the Soviets were improved after the Treaty of Tartu in 1920, in which Finland gained Petsamo, but gave up its claims on East Karelia.

After four attempts at instituting prohibition of alcohol during the Grand Duchy period, all rejected by the Tsar, independent Finland enacted prohibition on June 1, 1919. It lasted until April 5, 1932, and had many indisputably negative effects on Finns' drinking habits and on the crime rate in the country.[16][17]

Nationalist sentiment remaining from the Civil War developed into the proto-Fascist Lapua Movement in 1929. Initially the movement gained widespread support among anti-Communist Finns, but following a failed coup attempt in 1932 it was banned and its leaders imprisoned.

The Soviet Union started to tighten its policy against Finland in 1930s, limiting the navigation of Finnish merchant ships between Lake Ladoga and the Gulf of Finland and blocking it totally in 1937.

Finland in World War II

During World War II, Finland fought two wars against the Soviet Union: the Winter War of 1939–1940, resulting in the loss of Finnish Karelia, and the Continuation War of 1941–1944 (with considerable support from Nazi Germany resulting in a swift invasion of neighboring areas of the Soviet Union), eventually leading to the loss of Finland's only ice-free winter harbour Petsamo. The Continuation War was, in accordance with the armistice conditions, immediately followed by the Lapland War of 1944–1945, when Finland fought the Germans to force them to withdraw from northern Finland back into Norway (then under German occupation).

In August 1939 Nazi-Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, where Finland and the Baltic states were given to the Soviet "sphere of influence". After the Invasion of Poland, the Soviet Union sent ultimatums to the Baltic countries, where it demanded military bases on their soil. The Baltic states accepted Soviet demands, and lost their independence in the summer of 1940. In October 1939, the Soviet Union sent the same kind of request to Finland, but the Finns refused to give any land areas or military bases for the usage of the Red Army. This caused the Soviet Union to start a military invasion against Finland on 30 November 1939. Soviet leaders predicted that Finland would be conquered in a couple of weeks. However, even though the Red Army had huge superiority in men, tanks, guns and airplanes, the Finns were able to defend their country about 3.5 months and still avoid invasion successfully. The Winter War ended on 13 March 1940 with the Moscow peace treaty. Finland lost the Karelian Isthmus to the Soviet Union after the war. The Winter War was a big loss of prestige for Soviet Union, and it was expelled from the League of Nations because of the illegal attack. Finland received lots of international goodwill and material help from many countries during the war.

After the Winter War the Finnish army was in very bad shape, and needed recovery and support as soon as possible. Soon after the peace treaty was signed, the Finnish government tried to contact the British government to negotiate some kind of military alliance or support. However, the British government was not as interested about Finland's situation as it was during the Winter War, and no military contracts were made. In autumn 1940 Nazi-Germany offered weapon deals to Finland, if the Finnish government would allow German troops to travel through Finland to occupied Norway. Finland accepted, and weapon deals were made. In November 1940 in a German-Soviet meeting in Berlin, Soviet foreign minister Molotov asked Germany's opinion if Soviet Union re-attacked Finland.

Unlike the year earlier, Germany opposed the Soviet invasion of Finland. Nazi Germany suggested military co-operation for Finland in December 1940.

Finland's support from, and coordination with, Nazi Germany starting during the winter of 1940–41 and made other countries considerably less sympathetic to the Finnish cause; particularly since the Continuation War led to a Finnish invasion of the Soviet Union designed not only to recover lost territory, but additionally to answer the irredentist sentiment of a Greater Finland by incorporating East Karelia, whose inhabitants were culturally related to the Finnish people, although religiously Russian Orthodox. This invasion had caused the United Kingdom to declare war on Finland on 6 December 1941.

Finland managed to defend its democracy, contrary to most other countries within the Soviet sphere of influence, and suffered comparably limited losses in terms of civilian lives and property. It was, however, punished harsher than other German co-belligerents and allies, having to pay large reparations and resettle an eighth of its population after having lost an eighth of the territory including one of its industrial heartlands and the second-largest city of Viipuri. After the war, the Soviet government settled these gained territories with people from many different regions of the USSR, for instance from Ukraine.

The Finnish government did not participate in the systematic destruction of Jews, although the country remained a "cobelligrent", a de facto ally of Germany until 1944. In total, eight German Jewish refugees were handed over to the German authorities.

During and in between the wars, approximately 80,000 Finnish children were evacuated abroad. 5% went to Norway, 10% to Denmark, and the rest to Sweden. Most of them were sent back by 1948, but 15–20% remained abroad.

Finland had to reject Marshall aid. Nevertheless, the United States shipped secret development aid and financial aid to the non-communist SDP.[18] Establishing trade with the Western powers, such as the United Kingdom, and the reparations to the Soviet Union caused Finland to transform itself from a primarily agrarian economy to an industrialised one. After the reparations had been paid off, Finland continued to trade with the Soviet Union in the framework of bilateral trade.

Finland's role in Second World War was in many ways strange. Firstly the Soviet Union tried to invade Finland 1939–40. Even with massive superiority in army strength, the Soviet Union was unable to conquer Finland. In late 1940, German-Finnish co-operation had begun, and was unique when compared to relations with The Axis. Finland signed the Anti-Comintern Pact, which made Finland an ally with Germany in the war against the Soviet Union. But, unlike all other Axis states, Finland never signed the Tripartite Pact and so Finland never was de jure an Axis nation. In the Tehran Conference of 1942,the leaders of the Allies agreed Finland was fighting a separate war against the Soviet Union, and that in no way was it hostile to the Western allies. The Soviet Union was the only Allied country which Finland had conducted military operations against. Unlike any the Axis nations, Finland was a parliamentary democracy through the 1939–1945 period. The commander of Finnish armed forces during the Winter War and the Continuation War, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, became the president of Finland after the war. Finland made a separate peace contract with the Soviet Union on 19 September 1944, and was the only bordering country of USSR in Europe that kept its independence after the war.

Cold War

In 1950 half of the Finnish workers were occupied in agriculture and a third lived in urban towns.[19] The new jobs in manufacturing, services and trade quickly attracted people to the towns. The average number of births per woman declined from baby boom a peak of 3.5 in 1947 to 1.5 in 1973.[19] When baby boomers entered the workforce, the economy did not generate jobs fast enough and hundreds of thousands emigrated to the more industrialized Sweden, migration peaking in 1969 and 1970 (today 4.7 percent of Swedes speak Finnish).[19] The 1952 Summer Olympics brought international visitors.

Finland retained a democratic constitution and free economy during the Cold War era. Treaties signed in 1947 and 1948 with the Soviet Union included obligations and restraints on Finland, as well as territorial concessions. Both treaties have been abrogated by Finland since the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union, while leaving the borders untouched. Even though being a neighbour to the mighty Soviet Union sometimes resulted in overly cautious concern in foreign policy ("Finlandization"), Finland developed closer co-operation with the other Nordic countries and declared itself neutral in superpower politics.

In 1952, Finland and the countries of the Nordic Council entered into a passport union, allowing their citizens to cross borders without passports and soon also to apply for jobs and claim social security benefits in the other countries. Many from Finland used this opportunity to secure better paying jobs in Sweden in the 1950s and 1960s, dominating Sweden's first wave of post-war labour immigrants. Although Finnish wages and standard of living could not compete with wealthy Sweden until the 1980s, the Finnish economy rose remarkably from the ashes of World War II, resulting in the buildup of another Nordic-style welfare state.

Despite the passport union with Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Iceland Finland could not join the Nordic Council until 1955 because of Soviet fears that Finland might become too close to the West. At that time the Soviet Union saw the Nordic Council as part of NATO of which Denmark, Norway and Iceland were members. That same year Finland joined the United Nations, though it had already been associated with a number of UN specialized organisations. The first Finnish ambassador to the UN was G.A. Gripenberg (1956–1959), followed by Ralph Enckell (1959–1965), Max Jakobson (1965–1972), Aarno Karhilo (1972–1977), Ilkka Pastinen (1977–1983), Keijo Korhonen (1983–1988), Klaus Törnudd (1988–1991), Wilhelm Breitenstein (1991–1998) and Marjatta Rasi (since 1998). In 1972 Max Jakobson was a candidate for Secretary-General of the UN. In another remarkable event of 1955, the Soviet Union decided to return the Porkkala peninsula to Finland, which had been rented to the Soviet Union in 1948 for 50 years as a military base, a situation which somewhat endangered Finnish sovereignty and neutrality.

Finland became an associate member of the European Free Trade Association in 1961 and a full member in 1986. A trade agreement with the EEC was complemented by another with the Soviet Bloc. The first Conference for Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE), which lead to the creation of the OSCE, was held in Finland in 1972–1973. The CSCE was widely considered in Finland as a possible means of reducing tensions of the Cold War, and a personal triumph for President Urho Kekkonen.

Officially claiming to be neutral, Finland lay in the grey zone between the Western countries and the Soviet Union. The "YYA Treaty" (Finno-Soviet Pact of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance) gave the Soviet Union some leverage in Finnish domestic politics. However, Finland maintained capitalism unlike most other countries bordering the Soviet Union. Property rights were strong. While nationalization committees were set up in France and UK, Finland avoided nationalizations. After failed experiments with protectionism in the 1950s, Finland eased restrictions and made a free trade agreement with the European Community in 1973, making its markets more competitive. Local education markets expanded and an increasing number of Finns also went abroad to study in the United States or Western Europe, bringing back advanced skills. There was a quite common, but pragmatic-minded, credit and investment cooperation by state and corporations, though it was considered with suspicion. Support for capitalism was widespread.[20] Savings rate hovered among the world's highest, at around 8% until the 80s. In the beginning of the 1970s, Finland's GDP per capita reached the level of Japan and the UK. Finland's economic development shared many aspects with export-led Asian countries.[20]

Until 1970 Finland and other Nordic countries had relatively low taxes, low regulation, and some of the highest income levels in the world. Then Nordic countries saw a dramatic change. In Finland, the number of bureaucrats and overall taxation were doubled between 1970 and 1990.[21] Corruption became widespread in 1970s and 1980s.[22]

In 1991 Finland fell into a Great Depression-magnitude depression caused by a combination of economic overheating, fixed currency, depressed Western, Soviet, and local markets. Stock market and housing prices declined by 50%.[23] The growth in the 1980s was based on debt and defaults started rolling in. GDP declined by 15% and unemployment increased from a virtual full employment to one fifth of the workforce. The crisis was amplified by trade unions' initial opposition to any reforms. Politicians struggled to cut spending and the public debt doubled to around 60% of GDP.[23] Some 7–8% of GDP was needed to bail out failing banks and force banking sector consolidation.[24] After devaluations the depression bottomed out in 1993.

SDP suffered from its role in the crisis, though only few of the involved politicians aside from the SDP chairman Ulf Sundqvist were convicted. For the first time SDP gave voluntarily room for pro-Western Prime Minister Esko Aho, Finance Minister Iiro Viinanen and other opposition heavyweights to take care of the Finland's rescue operation.

Mauno Koivisto and later Tarja Halonen classified documents about their and other politicians' involvement in the crisis. Similarly, information about Stasi and KGB operations in Finland was classified, though revelations by former Soviet commanders, foreign intelligence services, and self-revelations have consistently pointed to top names such as Paavo Lipponen, the Prime Minister between 1995–2003.[25]

Recent history

The GDP growth rate has since been one of the highest of OECD countries and Finland has topped many indicators of national performance.

Until 1991, President Mauno Koivisto and two of the three major parties, Center Party and the Social Democrats opposed the idea of European Union membership and preferred entering into the European Economic Area treaty. However, after Sweden had submitted its membership application in 1991 and the Soviet Union was dissolved at the end of the year, Finland submitted its own application to the EC in March 1992. The accession process was marked by heavy public debate, where the differences of opinion did not follow party lines. Officially, all three major parties were supporting the Union membership, but members of all parties participated in the campaign against the membership. Before the parliamentary decision to join the EU, a consultative referendum was held on April 16, 1994 in which 56.9% of the votes were in favour of joining. The process of accession was completed on January 1, 1995, when Finland joined the European Union along with Austria and Sweden. Leading Finland into the EU is held as the main achievement of the Centrist-Conservative government of Esko Aho then in power.

In the economic policy, the EU membership forced large changes. While politicians were previously involved in setting interest rates, the central bank was given an inflation-targeting mandate until Finland joined the eurozone.[23] During Prime Minister Paavo Lipponen's two successive governments 1995–2003, several large state companies were privatized fully or partially. Matti Vanhanen's two cabinets followed suit until autumn 2008, when the state became a major shareholder in the Finnish telecom company Elisa with the intention to secure the Finnish ownership of a strategically important industry.

In addition to fast integration with the European Union, safety against Russian leverage has been increased by building fully NATO-compatible military. 1000 troops (a high per-capita amount) are simultaneously committed in NATO and UN operations. Finland has also opposed energy projects that increase dependency on Russian imports.[26] At the same time, Finland remains one of the last non-NATO members in Europe and there seems to be not enough support for full membership unless Sweden joins first.[27]

The population is aging with the birth rate at 10.42 births/1,000 population or fertility rate at 1.8.[19] With median age at 41.6 years Finland is one of the oldest countries [28] and half of voters are estimated to be over 50 years old. Like most European countries, without further reforms or much higher immigration Finland is expected to struggle with demographics, even though macroeconomic projections are healthier than in most other developed countries.

See also

- Finnish people

- History of Sweden

- History of Russia

- History of Europe

- History of the European Union

- List of Finnish wars

- List of Finnish treaties

- Monarchy of Finland

References

- ↑ Article on Helsingin Sanomat in English

- ↑ Article by professor of History of Religions Juha Pentikäinen at Virtual Finland [1]

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=QGqWcZu42hUC&pg=PA32&lpg=PA32&dq=comb+ugric&source=web&ots=9uRgOFQWjO&sig=Pkf9Kg0J7NZp04lWvU52SgUHeOM#PPA32,M1

- ↑ The common acceptance of the theory is indicated by the fact that this is the theory currently presented by the National Board of Antiquities in Finland, and several schools: E.g Tietoa Suomen esihistoriasta. Museovirasto. Retrieved 2008-03-20. (Finnish), SUOMEN ASUTUS- JA SIIRTOLAISUUSHISTORIA- PROJEKTI COMENIUS MIGRATION PROJEKTI. City of Helsinki. Retrieved 2008-03-20. (Finnish).

- ↑ Ante Aikio 2006: On Germanic-Saami contacts and Saami prehistory. – Journal de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 91: 9–55.

- ↑ Petri Kallio 2006: Suomalais-ugrilaisen kantakielen absoluuttisesta kronologiasta. – Virittäjä 2006.

- ↑ PEOPLE, MATERIAL CULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT IN THE NORTH Proceedings of the 22nd Nordic Archaeological Conference, University of Oulu, 18–23 August 2004 Edited by Vesa-Pekka Herva GUMMERUS KIRJAPAINO [2]

- ↑ http://www.kotikielenseura.fi/virittaja/hakemistot/jutut/2002_309.pdf

- ↑ Turun Sanomat

- ↑ http://www.folktinget.fi/pdf/publikationer/SwedishInF.pdf

- ↑ "National Archives Service, Finland (in English)". http://www.narc.fi/Arkistolaitos/eng/. Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- ↑ [Viklund, K. & Gullberg, K. (red.): Från romartid till vikingatid. Pörnullbacken – en järnålderstida bosättning i Österbotten, Vasa, Scriptum, 2002, 264 pages. Series: Acta antiqua Ostrobotniensia, ISSN 0783-6678 ; nr 5, and Studia archaeologica universitatis Umensis, ISSN 1100-7028 ; nr 15, ISBN 951-8902-91-7.]

- ↑ Forsius, A. Puujalka ja jalkapuu. Cited 2006-12-14. In Finnish

- ↑ Jyväskylän yliopiston kirjasto. Kielletyt kirjat. Cited 2006-12-14. In Finnish

- ↑ Suomen historia: kirkon historia Cited 2006-12-14. In Finnish

- ↑ Vihreä liitto. Päihdepoliittinen ohjelma 2003 Retrieved 2007-02-26. (Finnish)

- ↑ Municipality of Taivassalo. Salakuljetusta saaristossa Retrieved 2007-02-26. (Finnish)

- ↑ Hidden help from across the Atlantic, Helsingin Sanomat

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Population development in independent Finland – greying Baby Boomers

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Growth and Equity in Finland, World Bank

- ↑ [http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/48/59/1910873.pdf FROM UNIFORM ADMINISTRATION TO GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT OF DIVERSITY – Reforming State functions and public administration in Finland], OECD

- ↑ The History of Corruption in Central Government By Seppo Tiihonen, International Institute of Administrative Sciences

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Inflation targeting: Reflection from the Finnish experience

- ↑ Converted

- ↑ "Vasemmaltaohi", by Alpo Rusi

- ↑ Nato: Address by Mr Pertti Torstila, Secretary of State, to the Macedonian Diplomatic Bulletin

- ↑ Finland and NATO, Tomas Ries.

- ↑ Median Age (Years) – GlobalHealthFacts.org

Further reading

- Jussila, Hentilä, Nevakivi. From Grand Duchy to a Modern State: A Political History of Finland Since 1809 (Hurst & Co. 1999).

External links

- History of Finland – World History Database

- Finnish historical documents at WikiSource (Finnish)

- History of Finland: A selection of events and documents by Pauli Kruhse

- History of Finland: Primary Documents

- Diplomatarium Fennicum – Publishing of medieval documents (the National Archives of Finland)

- ProKarelias collection of international treaties concerning independent Finland (Finnish)

- Historical Atlas of Finland

- Vintage Finland - slideshow by Life magazine

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||